MOZART

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

(1756–1791)

Concerto Grosso Frankfurt Orchestra – Serenata Notturna in D major

Eden Court, 1997

The Serenata Notturna dates from January 1776 when Mozart was in the employ of the humourless Archbishop Colloredo at Salzburg. Despite pining for the wider musical horizons of Vienna and Paris, where he had scored such glittering success as a child prodigy, no hint of this frustration finds its way into his music, and he was kept as busy as ever.

The first half of the year was taken up with composing, among other things, numerous divertimentos (basically, background music) and serenades. Of the five serenades he wrote to August 1776, all are in the key of D, but the Serenata Notturna is the only one scored for timpani and strings (rather than winds and strings) – the major group being made up of two violins, viola and double bass.

Serenades were originally love songs, but by the late 18th century the term had evolved to mean a set of movements for chamber orchestra especially designed to be played in the open air in the evening. The kind of celebrations requiring music included weddings, graduations and the like, and since Salzburg high society at the time took its pleasures both seriously and frequently, Mozart and his colleagues were constantly being called on to provide a steady stream of light, frothy works. But musicologists have recognised that Mozart subtly adapted and developed these for his own ends.

The idea of such music was to chime in with the festive mood and generally underscore the Arcadian good cheer of the moment. Mozart duly employed the outer movements of his serenades to create an atmosphere of great exuberance, but only the better to introduce into the slower Minuet section an unwonted edge of melancholy or pathos through the use of minor keys.

These still provided the grace and harmony required, while the fast dance sections retained a bounce and life totally devoid of the kind of rustic vulgarity or coarseness such movements were prone to. In this way, for all its grace and formal perfection, Mozart’s music still displays a surprising solidity and strength, and a refreshing lack of sentimentality. As Maynard Solomon puts it in Mozart: A Life: “The serenade was a vehicle in which he could participate in the rough-and-tumble of the world, give vent to erotic yearnings, focus attention on loss and mourning, show the interpenetration of opposing deep feelings that lie just beneath the green Arcadian turf.”

Interestingly, although so many serenades were written at this period by Mozart and others, relatively few survive. This was because the form was intended for a single performance only. Nevertheless, they could be surprisingly large in scale, with an opening and closing march encompassing several Minuets and a similar number of slow movements, usually scored for an orchestra of up to a dozen players.

Once he had left Salzburg, however, Mozart’s own output in the form slowed to a trickle. This was not simply because he was busy with other things; it was as if, for him, the serenade symbolised Salzburg and once he had moved on, he felt no desire to look back. Perhaps the greatest example of his serenade style from later years is Eine kleine Nachtmusik (Serenade No 13 in G), usually translated as ‘A Little Night Music’ but which more properly perhaps should be thought of as ‘A small serenade’.

Concerto Grosso Frankfurt Orchestra – Piano Concerto in A major

Eden Court, 1997

Mozart’s move to Vienna in the spring of 1781 unlocked a fresh flood of inspiration. As well as producing the opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail, the six Haydn Quartets and the C minor Mass, during his first years in that city he virtually invented the classical piano concerto. Between the autumn of 1782 and December 1786 he wrote well over a dozen of them, from No 11 in F, K413 to No 25 in C, K503. Each is unique in style and content, even though he was often working on several at the same time, and for both quality and originality they are generally agreed to be among the most astonishing achievements in the entire canon.

It is therefore interesting to note that they were written as much for money as for reasons of creative impulse. Recently married to Constanze Weber, and as ever short of funds – particularly since he had now sloughed off the dead hand of his former Salzburg patron Archbishop Colloredo – Mozart went into the impresario business, setting up subscription concerts with himself as the main attraction.

Response to the early shows was good, so by early 1783 he had completed three new concertos to play. Although the subscriptions generated rather less income than he had expected, he hoped to earn more by upping the number of concerts he gave. This was highly irregular in Vienna, not least because few composer-soloists could turn out the new material required as quickly as Mozart. So the novelty and range of the concertos was as much in response to the need to dazzle his subscribers and ensure their return as it was an objective desire to extend the possibilities of the form. But perhaps Mozart’s greatest achievement throughout this enterprise was to find a way of pleasing all shades of his largely aristocratic audience, some of whom were knowledgeable enough to appreciate his invention, while the rest merely went to musical entertainments because it was the sort of thing the rich did, like going to the opera today.

Of this first group of three new concertos the composer boasted in a letter to his farther: “They strike a happy balance being neither too easy nor too difficult; they are quite brilliant, pleasant on the ear and natural without being empty. They contain occasional passages which only connoisseurs can appreciate, yet even these are written in such a way that less learned folk couldn’t fail to enjoy them, although they might not realise why.”

The Concerto in A major, K414, is generally thought to be the most impressive of the trio and it displays Mozart’s usual fertility in melodic invention going hand in hand with an understated virtuosity in the piano part. Some have identified in the main theme of the Andante a reference to the overture La calamita dei cuori by JC (‘the English’) Bach, who had only recently died, and the music’s elegiac character has been interpreted as an act of homage.

He also wrote two Finales, of which a Rondo has been taken to be a rejected first attempt. The one enshrined in the score is delicate in nature, and like the discarded effort, is an Allegretto in 2/4 time, indicating that the composer had a clear idea of the kind of feeling he wanted to convey before he hit upon the most appropriate means of expressing it.

Concerto Grosso Frankfurt Orchestra – Quintet in E flat

Eden Court, 1997

In February 1784 Mozart began writing a catalogue of his works, noting down the date on which they were completed and identifying each piece with a sketch of the opening bars. The sheer number and variety of his compositions over the period indicates that, for all the serenity and formal perfection of the works themselves, they were being churned out by a man in a fever of frenetic activity. In that one year alone the catalogue lists six piano concertos, a string quartet, two sonatas, two sets of piano variations, several smaller compositions, and the Quintet in E flat for keyboard and winds.

Three of these concertos and the Quintet were composed between 9 February and 12 April, a nine-week span during which Mozart gave no fewer than twenty-four concerts. But it wasn’t only his new-found role as a composer-performer-impresario that was taking up his time. Apart from the subscription concerts, and those he gave in private houses, he also had numerous teaching commitments, as well as the distractions of two changes of residence and numerous house guests. With all this to do,” he wrote laconically to his father in March, “I doubt it’s likely I shall ever get out of practice.” For all that, he never defaulted on a single invitation to dine out with friends or enjoy some other social diversion. It was as if he thrived on pressure, and the moments of relaxation were necessary to recharge his batteries.

The Quintet in E flat was premiered on 1 April at the Burgtheater in a programme which also included two new piano concertos (in B flat and Dm, K450 and 451). However, it was the Quintet which attracted the greatest acclaim. Perhaps still buoyed up by this wave of enthusiasm, Mozart reported to his father that the Quintet was “the best work I have ever composed.”

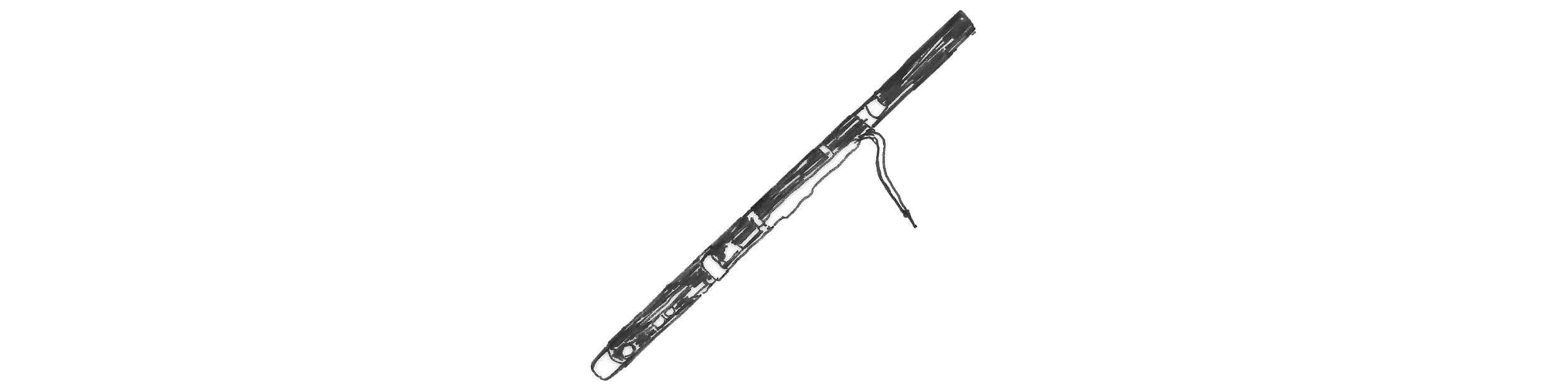

Chamber music on this small scale can often sound thin. In the Quintet the solo keyboard is allied with the oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn, all wind instruments which cannot easily sustain a prolonged line. Mozart overcame this potential hazard by using his melodic material in short phrases, creating and resolving tensions rapidly, and it was no doubt this inventiveness and resource that the Viennese public recognised and responded to.

The following year was to prove just as hectic for the composer, but it was also the year in which he would receive the famous plaudit from his friend Joseph Haydn which was to do the utmost credit to both men. That February, after an evening of chamber music in Mozart’s home, Haydn told the composer’s father: “Before God and as an honest man I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me either in person or by name.” Posterity has tended to agree.